Collaborative Behaviour Trees in a Games Commons

July 2, 2025

The Commons is property that opens itself up to use by anyone, and which is owned and managed by the people who use it… So what would that mean when talking about AI in game development?

For the past couple of years I’ve been working on the concept of a Games Commons, which is a new way of designing games that centres around the principles of flexibility, collaboration and Do-It-Together. These are games built around a creative community of hackers, like Wikipedia but for game content.

Our flagship game is about making and breaking social systems. In-game, social systems are made up of networked agents that are running AI scripts built by players, shared in common and quality-reviewed by communities. The design of the tools which enable the player to create and collaborate on such scripts is the subject of today’s article.

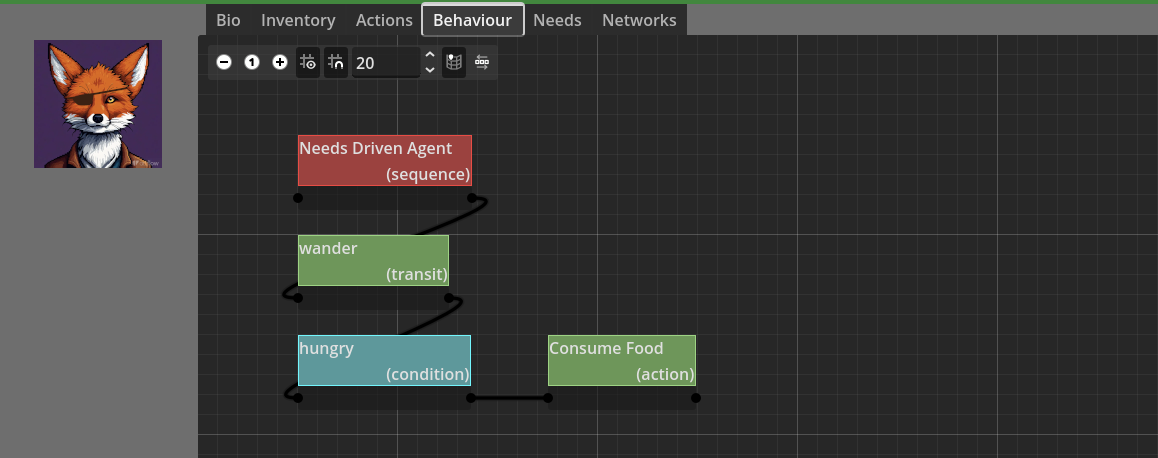

The interface is very much a work-in-progress.

Agents need an AI script for decision making; put simply it tells them what to do next. We sometimes assume AI in games is strategic: the agent could be a peer of the human player, working with or against them. At the other extreme, though, the agent may be there simply to decorate the world and make it believable. Usually a single game will employ several different kinds of AI, each serving different purposes. “Good game AI” is therefore not necessarily AI which is strategic or adaptive enough to pass the Turing test; it’s AI which is appropriate to the objectives of the game designer for the agent that is deploying it.

The design of Sim Polis revolves around flexible systems that are evolving with player interaction, and the AI as such needs to be adaptable to the “open world assumption” (meaning, anything is possible.) It’s not enough to have an apple merchant show up in the town square every morning expecting to sell his apples, if due to player interaction apples are now widely believed to be poisonous by the townspeople. Better than not showing up at all, the apple merchant should show up in the town square and start to argue with the townspeople, possibly ending in his arrest. Flexibility like this is challenging enough, but we also need a structure accessible enough that players can create and share these this scripts themselves via the interface. Our approach to achieving these goals will be to use a modular design for our AI, relying on abstraction.

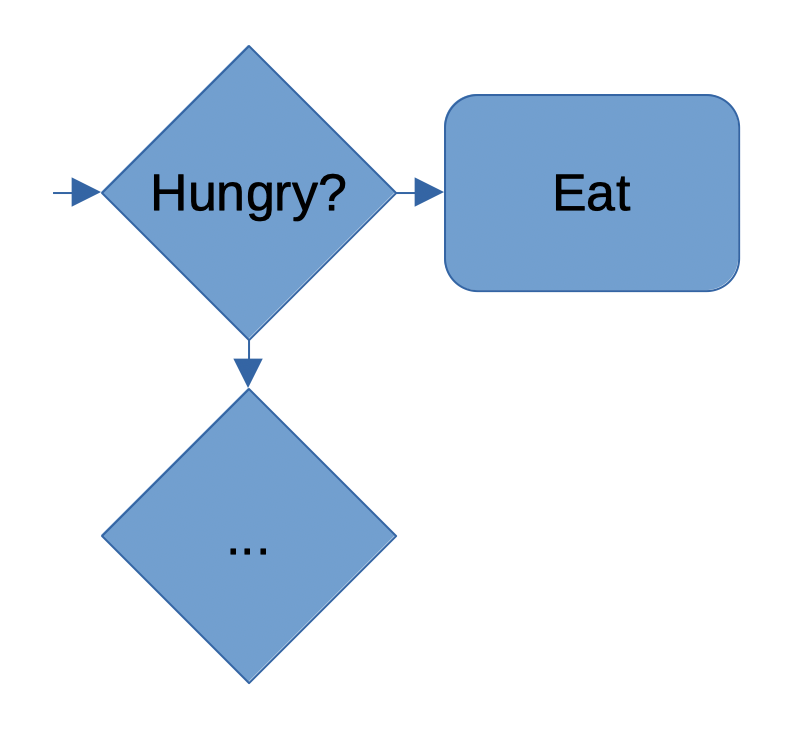

Behaviour Trees are essentially flowcharts that direct the decisions to be made and the actions taken by an agent. A simple behaviour tree might instruct an agent to eat if it is hungry:

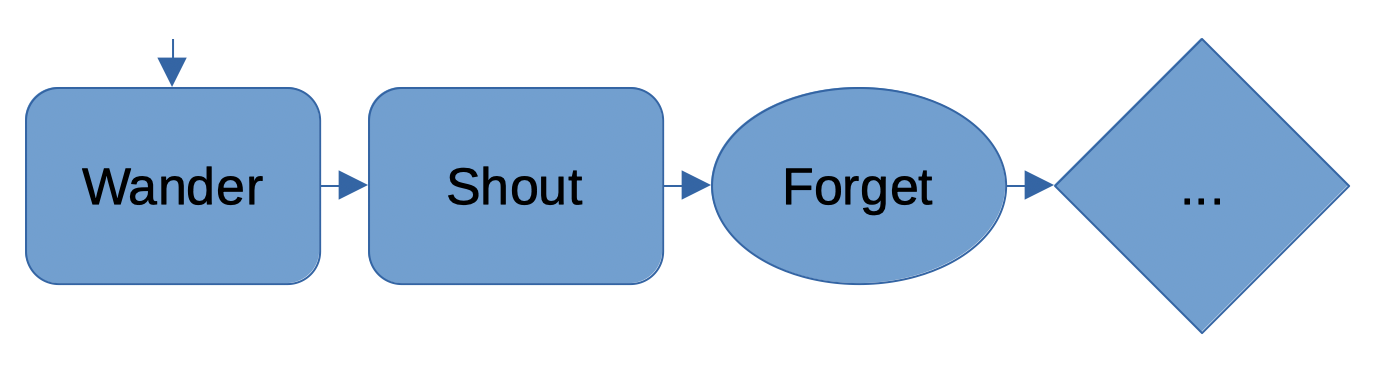

The tree here begins with the control node “is the agent hungry?”. If the agent is hungry, it would execute the action node: “eat something”. If the agent is not hungry, it would follow the other side of the tree. The result is that hunger is prioritised. If the agent is not hungry, then the flow continues. We can imagine a situation where (relieved of hunger) the agent is free to subsequently pursue a more whimsical chain of behaviours:

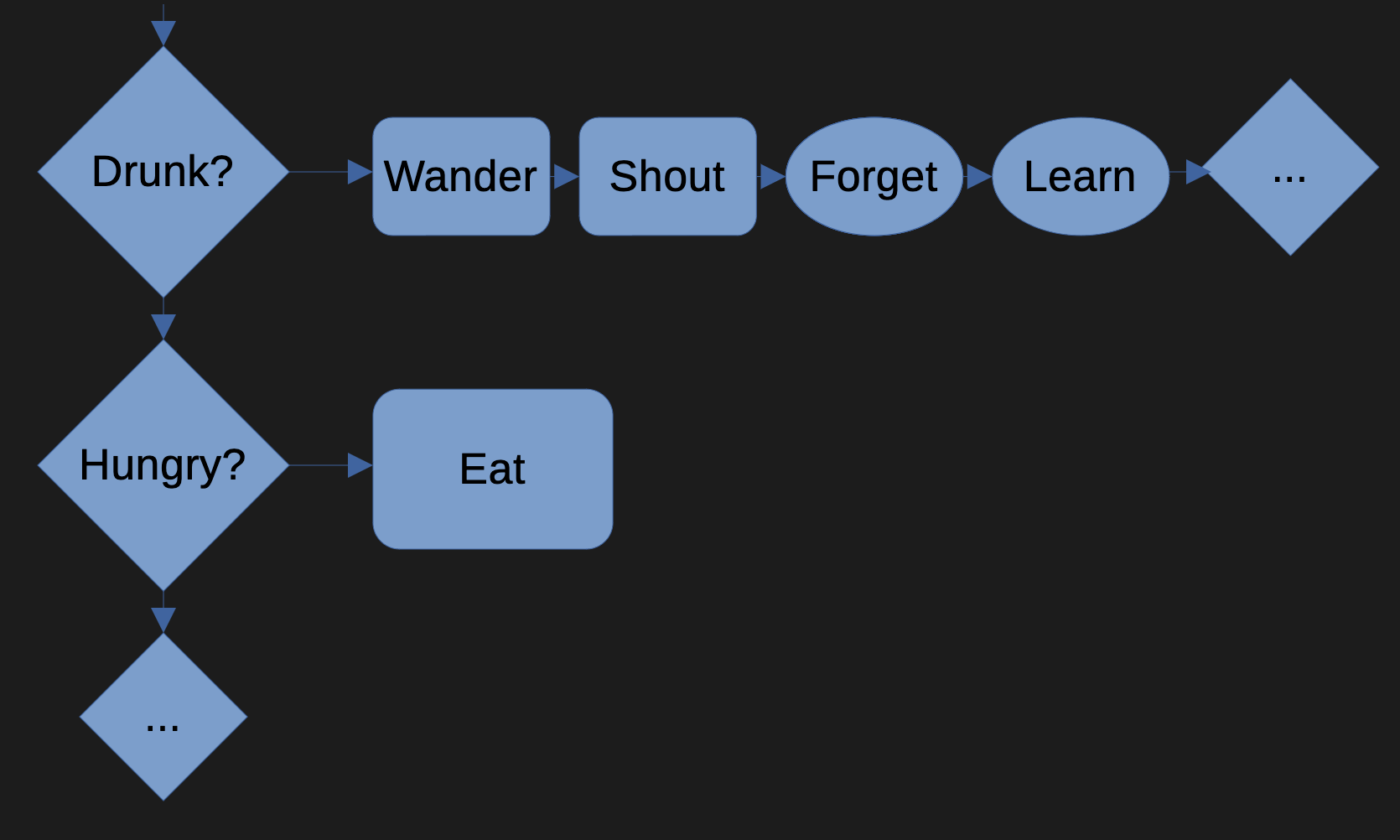

In the example above the agent will wander, and then shout. This branch of the tree finishes with a forget node, a special kind of control node for permanently modifying the behaviour tree itself. Execution of this node will destroy the wander-shout sub-branch, since the behaviour should be executed once - it was intended to be whimsical; a moment of madness. It also demonstrates that behaviour trees are modular; we can imagine the wander-shout branch being sufficient to define the entire behaviour tree of a raving lunatic, but for another agent we could plug in the same branch as just one aspect of their behaviour:

If the agent is drunk, they wander, shout and forget, before executing a new node, “learn”. If the player is not drunk, the chart moves on to the hunger condition from the first example. We can see here how the behaviours wander-shout-forget, and hunger-eat, have been packaged into branches. Once packaged, they can be re-used by their creator in the behaviour trees of different agents, and published online with some metadata about what the branch does. Once published online other players can import the behaviour into their own agents, which is a powerful mechanism for building a games commons. Further from this we have the “learn” node, which with the right metadata, can use search parameters for the agent to discover a new drunken behaviour online from the games commons. The next time this tree executes and the agent is still drunk, he will have forgotten the wander-shout behaviour but may discover a behaviour someone has published on the games commons that causes him to fall over and begin singing.

The fact that the nodes in our behaviour trees are driven by data that can be published and then discovered at run time allows for the emergence of spontaneous and unique behaviour that isn’t conceivable in traditional game design. The flexibility of the behaviour tree system within the social technology of a Commons allows for the design of games which can evolve with the creativity of its player base.